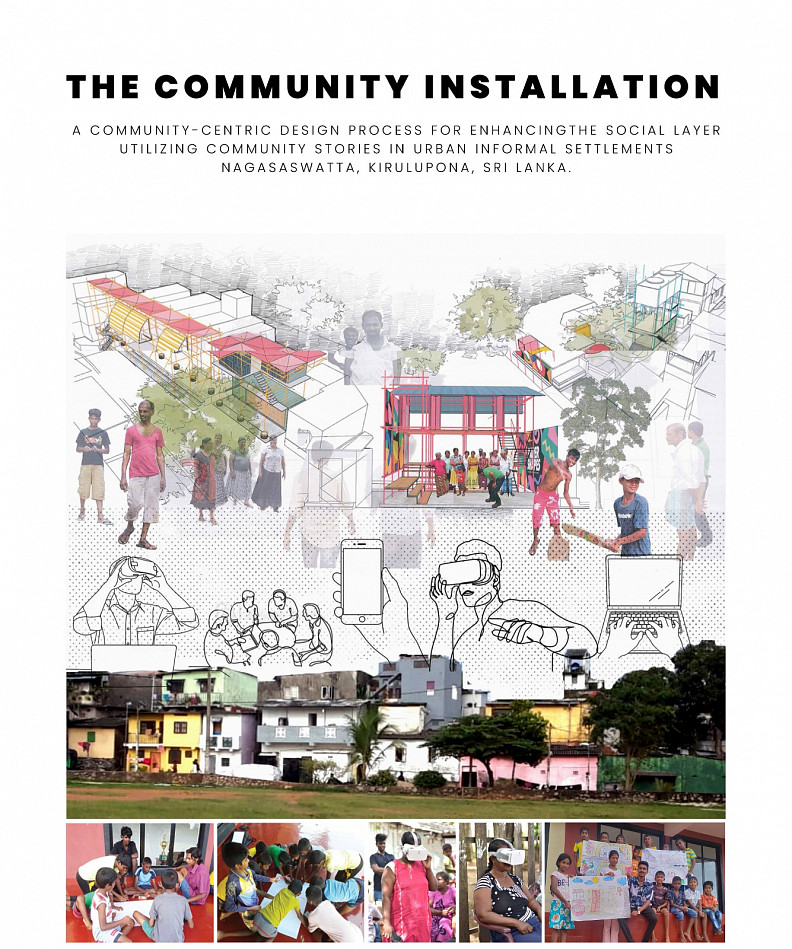

THE COMMUNITY INSTALLATION

Project idea

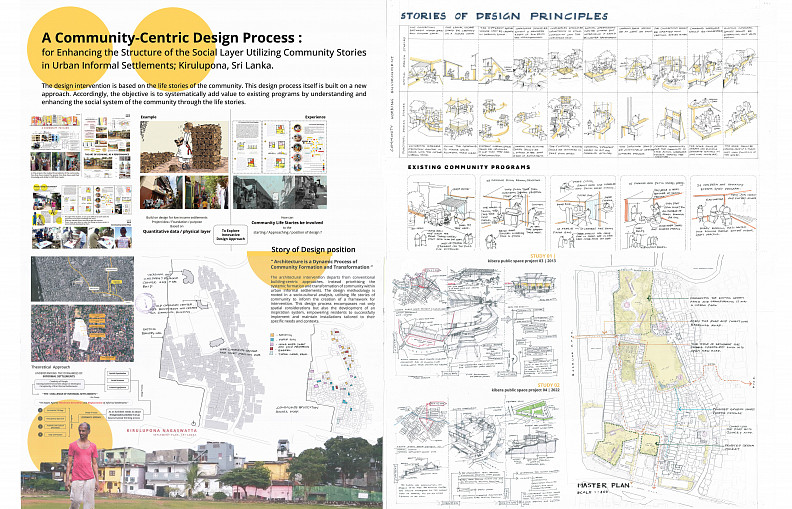

The design thesis investigates the life stories of communities in urban informal settlements and through the stories, identifying the structure of their social systems and enhancing social layer through supportive architectural systems. The persistent phenomenon of community rejection of government development projects within urban informal settlements. A critical analysis reveals that the prevailing governmental design process, characterized by a reliance on quantitative data and a primary focus on the physical layer, fails to adequately address the socio-cultural system of these communities. Consequently, the building programs implemented often exhibit a significant disconnect from the community's inherent socio-cultural programs, leading to project incompatibility and subsequent rejection.

The research advocates for a participatory design process to urban informal settlement transformation, positing that the elicitation and mapping of community life stories constitutes a fundamental design process for understanding and enhancing endogenous social systems. Rather than imposing typical systems or building a building solution, the research prioritizes the capture of community essence, values, community networks, and shared experiences, thereby establishing a design process that aims to elevate social dignity and foster resilience within these communities.

Project description

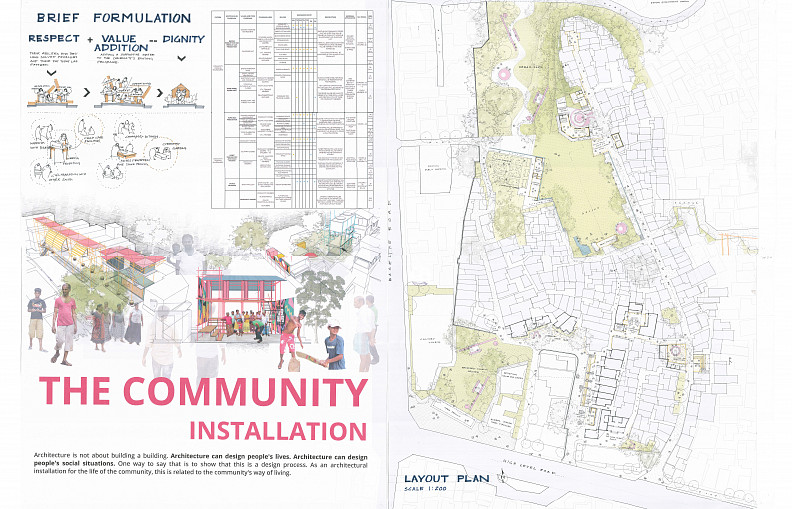

“ Architecture is not about building a building.

Architecture can design people's life, Architecture can design people's social situations. ”

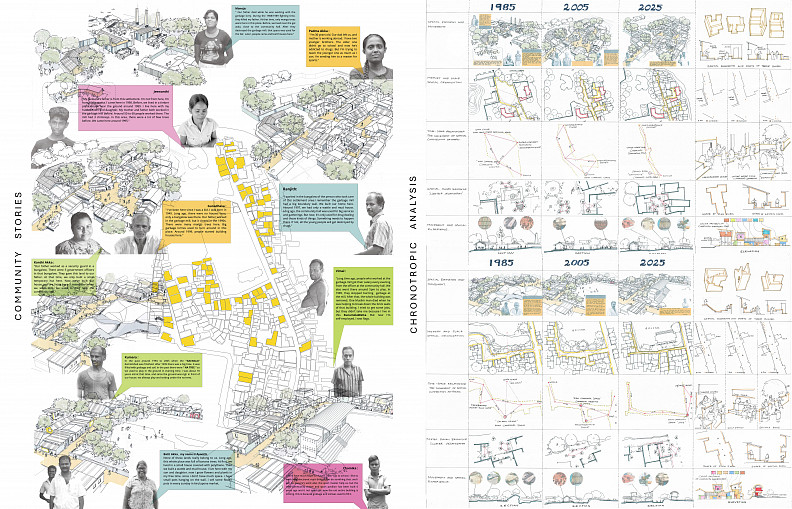

The settlement of Nagaswatta is situated in Colombo 04, Kirulapana, within the Western Province of Sri Lanka. Established in 1962, the initial development of this community was closely linked to a local dump mill and quarry. This section will evaluate the settlement in relation to its origins as a work-based community.

Between 1985 and 1990, the dump yard ceased operations, and the quarry was exhausted by 1999. Consequently, the primary means of income for the settlement underwent a significant transformation. Initially, income generation occurred within the settlement itself. However, from 2000 to 2005, the community's income-generating methods shifted, with residents increasingly seeking employment outside of Nagaswatta. These jobs commonly included cleaning services, garbage collection, and housekeeping. This transition contributed to complex issues of social dignity and social stigma within the community. Currently, Nagaswatta comprises 264 families, with a total population of 1364 individuals. Approximately 420 residents hold permanent positions in security and cleaning services. Additionally, there are 24 families where women are self-employed, engaging in activities such as snack packing, paper bag creation, and sweet making.

The foundation of this approach is derived from the accumulated experiences and interconnected design projects undertaken throughout the university's five-year curriculum. Consequently, a significant emphasis has been placed on the social dynamics of communities residing in urban informal settlements in Sri Lanka. This design thesis extends and elaborates upon this established focus. The several common issues emerged in all these projects. Among them, it should be noted that with the passage of time, the development buildings provided by the government, especially in informal settlements, have been rejected by the community, and they have been tempted to find solutions based on their own methods. Identifying a gap and a new design method here is built through the design thesis. Accordingly, the design brief is discussed by identifying the social structure through the life stories of the community in informal settlements and forming it.

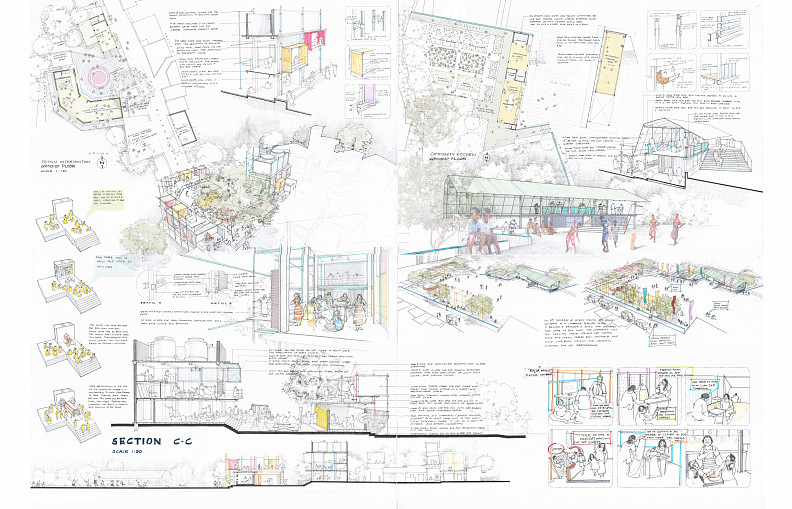

This design project employs a community-centric approach rooted in a Community Participatory Design process. The methodology involves identifying the existing social structure and enhancing the lives of the community members through a study of their stories and experiences. The aim is to add value that is meaningful and relevant to their way of living.

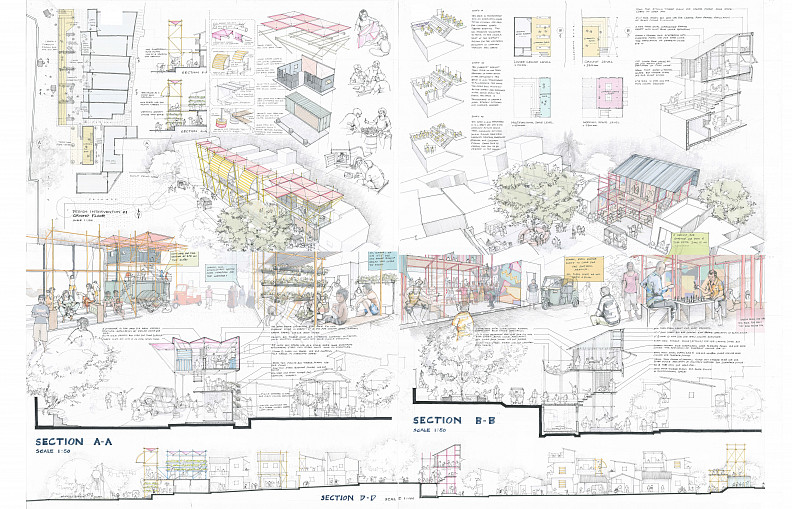

The stories of the community are intangible feelings, and they tell the way they live, the social problems they face, and the memories of the past through those stories. Accordingly, it is necessary to convert those stories into a tangible formation. Through that, a design approach can be taken. Accordingly, the method of chronotropic analysis was used for this. Through that, the stories of the community are converted into a 2D formation. In it, the special organization, the special connection of spaces, the special moment, and even the material itself are understood. Accordingly, their two basic spaces, the garbage-burning mill and the stone, are built on the basis of their economic situation and social life have been built within the settlement itself. However, the government has provided a vocational training center building and a community center without any understanding of this. However, over time, the community has rejected both those buildings.

Through the stories of the community, the pattern of their social life is understood. Then the principles required to build design innovation are built. Those principles are filed as special design stories and functional digital stories and the principle stories that are inherent to them are collected. Through this, it is very important to establish the social environment for the working environment of the user. Accordingly, an architecture systematic plugin is added to the social pattern of the community without knowing it. Accordingly, the design thesis points out a new method to enhance the social dignity of the community in such informal settlements. Where the design intervention transforms their social life by adding a value addition to the existing social process. Through this, integration with other social layers, development of social capital and opening up new opportunities occur.

Technical information

Community Action Plan workshop ( CAP)

The design process used community stories to understand community members' ideas. First, stories were gathered from the elders as part of the Community Participatory Design. Then, to think about the future, a workshop was held with children (Grades 6-12). Children were asked how children could add value to the community and settlement in the future. In three groups, children discussed hopes and then drew future homes and Settlement based on the play ground together.

Observing the children, it was clear children valued ground-level spaces like green areas, paths, and playgrounds. Children also had new ideas, such as turning the old community center into a gym. Children's drawings showed detailed visions of these future places. When looking at all the drawings, common ideas appeared. Children often thought about what children could do in each space, like playing in the park. Children's dreams were very specific about activities. Children's everyday interactions and experiences have shaped the understanding and influenced the value children hope to bring to the community in the future.

The Material evaluation was informed by the stories and existing built environment of the community. The current material palette predominantly consists of brick walls, timber, galvanized iron (GI) sheets, and asbestos cement (Amano) sheets. This design intervention aims to enrich their existing material palette through the thoughtful introduction and innovative application of zinc-aluminum sheets, timber, scaffolding elements, fabrics, GI pipes, and concrete. These materials are selected and employed in a manner that reflects the character and sense of the community. By strategically utilizing these materials, the design seeks to enhance the perceived value and dignity associated with their built environment.